The National Enquirer, Elvis Presley and Me

My three brief encounters with the notorious tabloid

The National Enquirer — that publication that straddles the worlds of sensationalism, fiction, propaganda and journalism — is dominating the news cycle thanks to Donald Trump’s hush money trial now underway in Manhattan. We’re learning all about the Enquirer’s style of checkbook journalism1 and its unwritten motto, “Never Let the Facts Get in the Way of a Good Story.”

It brings to mind three separate encounters I had with the National Enquirer in my life (or two-and-a-half, depending on how you’re counting).

At some point in my life, I became aware of the Enquirer while waiting in line at a supermarket. Back in the 60s, it was probably one of those famously lurid headlines, like “I Cut Out Her Heart and Stomped On It.” Who among us hasn’t been titillated by an Enquirer headline while enduring a long line at checkout?

Through the years, the Enquirer remained an oddity, but a ubiquitous one. Its retail presence and technicolor covers made it hard to miss. Eventually I went into journalism, where ethics, standards and proper etiquette were drilled into me, and my attitude toward the Enquirer shifted from fascination to condescension.

After several years of toiling away at a mid-sized suburban daily newspaper I’d become a little disillusioned (“grizzled” would be a preferred newspaper adjective) with long nights covering City Council meetings and paychecks that barely covered my bar tab.

One day I saw an ad taken out by the Enquirer that it was hosting two days of open interviews for reporting positions, with a salary that was nearly triple what I was earning at the time.

I bit. Mostly out of curiosity, but also with the notion in the back of my mind that it might be kind of fun to report on triple murders and UFOs instead of planning permits and assessment fees, and also be able to buy a new car. I showed up for my interview in a hotel room at the Hyatt Regency in downtown San Francisco.

The hiring editor looked grizzled. I was probably his 10th interview of the morning. He had resumes scattered over the table between us. He looked like a nondescript copy editor who’d had too much coffee. His shirt was a shade off of white, either because of age or a substandard laundry. He looked bored as I sat down.

After I briefly described what I did and why I wanted to work for the Enquirer, to which he listened as if I was a fly droning somewhere off in the corner of the room, he leaned forward and his energy level picked up.

“What I want to know is whether you have the stuff we need in an Enquirer reporter,” he said. “Do you have what it takes?”

I started to ask him what it took, but he was already on a roll.

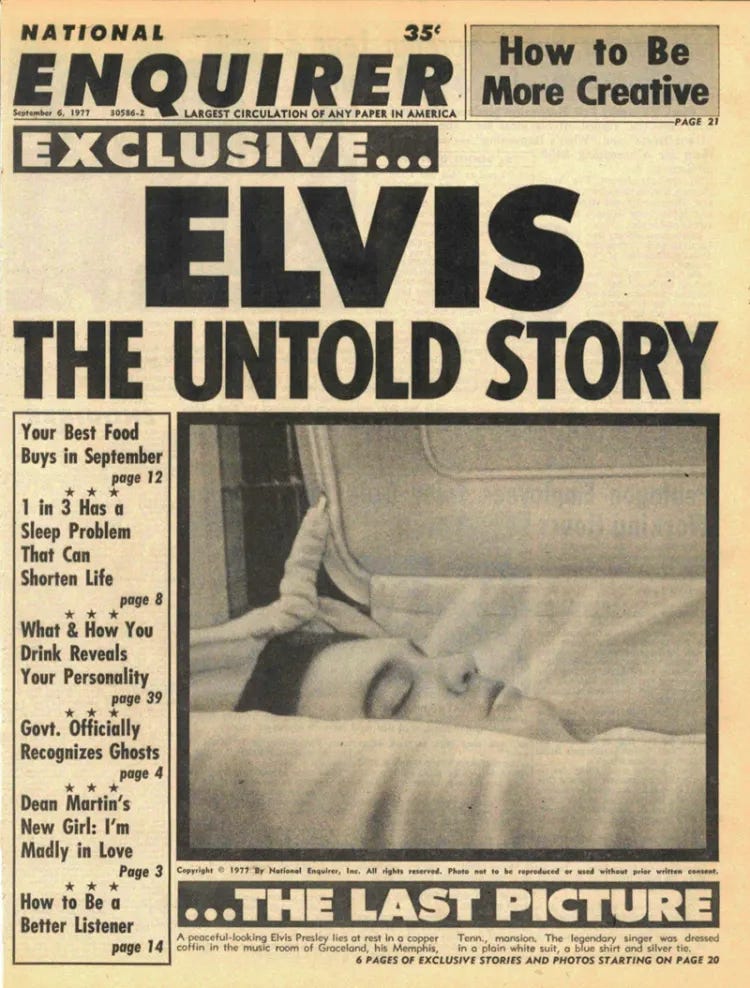

“We’ll do anything to get the story we want,” he said. “When Elvis died, we were the only publication to have a photo of him lying in his casket. When we want the story we figure out a way to get it.”

He then went on to tell me how the Enquirer got the shot. Elvis’s funeral and casket viewing were attended by more than 80,000 people in Memphis, but cameras were forbidden. Using a ruse that could have been thought up by Ben Hecht in “The Front Page,” an Enquirer reporter dressed up as a priest with a camera hidden in his vestments, and got in line for the viewing.

“That’s the kind of stuff we ask our reporters to do,” he told me. “Could you do something like that?”

Never having remotely considered impersonating a priest to get a story, I probably fumbled some kind of answer, and the interview quickly came to an end. Only much later did I find out how the Enquirer actually got the iconic casket shot. The undercover priest, it turned out, fumbled the camera and came back with nothing. So, the Enquirer defaulted to a tried-and-true tactic: the checkbook. It located one of Elvis’s cousins in a nearby bar and paid him $18,000 for a photo. Checkbook journalism may not be ethical but it’s effective.

Years later, I abandoned journalism for a public relations career at Bank of America. I helped launch a community development bank at one point, whose wheelhouse was lending to small businesses, particularly in distressed communities. I fashioned it into a story of boot-strapping, self-reliance and transformation — the American Dream, essentially.

We got decent media coverage. But it was supercharged when the clipping service picked up a story the National Enquirer had done on one of the bank’s clients — a single mom — who started a bakery in San Francisco with a Bank of America loan. At that point, the Enquirer was one of the largest-circulation weekly newspapers in the country, with more than 6 million readers. For a young publicist, working at a time when there was no Internet and the word viral was only used in a medical context, it was a walk-off home run.

I lost track of the Enquirer after that except when it would break the occasional story, like John Edwards’ love child or OJ’s incriminating Bruno Magli loafers. By that time the paper was being run by David Pecker and a magazine conglomerate called American Media. That’s when it entered the truly tawdry years, marked by lawsuits, apologies, stories made up out of whole cloth, and, of course, the unseemly relationship with Trump.

A chance encounter with David Pecker was my last interaction with the Enquirer.

I was coming out of Elio’s, a neighborhood restaurant on New York’s Upper East Side, as Pecker was coming in. By this time, he’d become a celebrity in his own right.

“Mr. Pecker!” I said. “How ya doing?”

Startled a little, he hesitated while he sized me up, then replied, “Fine, thanks,” and moved on. I’m sure he was waiting for a pie to be thrown in his face.

“Catch-and-kill” was a practice that began early in the Enquirer’s history, according to Wikipedia. By 1952, when the paper's circulation had fallen to 17,000 copies a week, it was purchased by Generoso Pope Jr., the son of Generoso Pope, the founder of Il Progresso, New York's Italian language daily newspaper. Pope's son Paul alleged that Luciano crime family boss Frank Costello provided Pope the money for the purchase in exchange for the Enquirer's promise to list lottery numbers and to refrain from any mention of Mafia activities

If I recall correctly (more and more iffy these days) the Enquirer paid a coroner night watchman a staggering amount to let a photographer into the room, for exactly one minute, where slain John Lennon lay on the slab. On a lighter note, the late SF Chronicle reporter Bill Wallace used to have us in stitches regaling the newsroom with his time as an Enquirer reporter on the 24-7 Jackie Kennedy Onassis stakeout in Manhattan!

As Elvis’ #1 fan, this story ticks me off. I hope Elvis is haunting his cousin’s dreams and this trial’s outcome (for various reasons for the latter 😎).