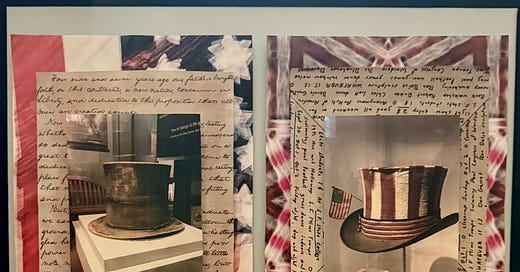

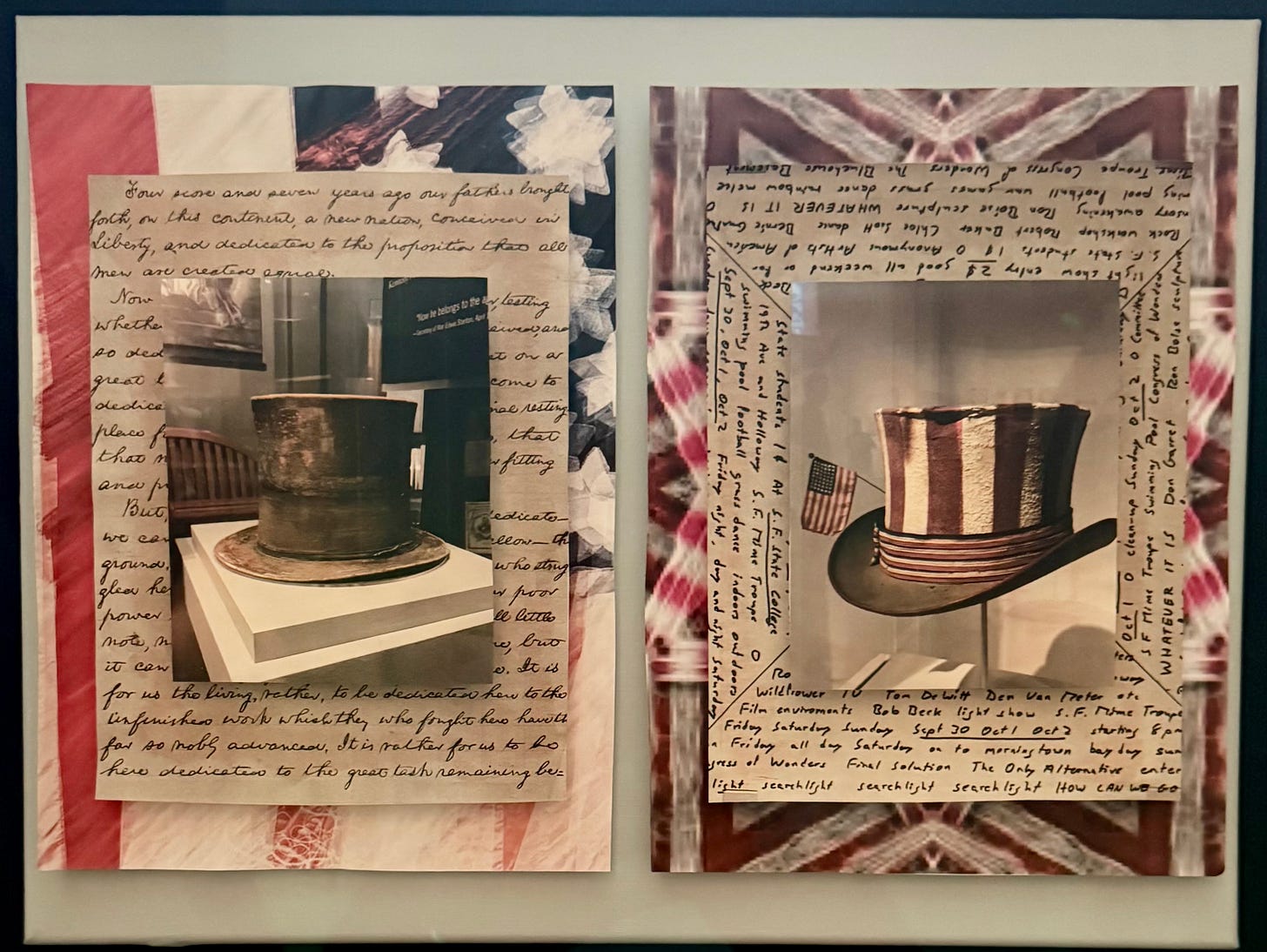

I have a piece of art I made several years ago hanging in the house called “Two Americas.” It’s an amateurish attempt to connect two figures in history who tried to define a new vision of freedom in America, each in their own way — Abraham Lincoln and Jerry Garcia. It was inspired partly by my obsession with the Grateful Dead, but even more so by my love of country and what it’s continually striving for — a more perfect union grounded in freedom and the infinite horizon of human aspiration. Both Abe and Jerry would understand what I mean.

This Fouth of July marks the one-year countdown to the semiquincentennial celebration of American freedom, the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. So, I decided to take a moment to revisit the core document of the American experiment. Like the Gettysburg Address, another consequential vision of America, the Declaration is short, coming in at less than 1,500 words. Its rhetoric soars from the lofty heights (“We hold these truths to be self-evident”) to arcania (quartering of troops, onerous food and beverage expenses, etc.), but overall, it majestically captures the moment when the American IPO was launched. The world was never the same afterward. Reading it left me swooning in the scope of its vision and the depth of its courage.

We’re swooning today, but for other reasons. At this milestone in American history, we’re more ambivalent and agitated about our country than we’ve been in the past five decades. Polarization is at historical highs. The poetry of Lincoln and the bliss of an extended Garcia lead in some version of “Dark Star” have been eclipsed by the snark and cynicism of social media, the perfidy of mainstream media and the rise of performance over substance in our politics.

This moment in time — or at least a portion of it — was captured in a new Gallup poll that measures pride in America. It’s not encouraging. A record-low 58 percent of U.S. adults say they are “extremely” (41 percent) or “very” (17 percent) proud to be an American, down nine percentage points from last year and five points below the prior low from 2020.

The political divide, otherwise known as the Trump effect, is stark. While Republicans say they are overwhelmingly proud to be American, pride among Democrats has virtually collapsed. Among Independents, the vast central core of America, American pride has dipped, but on a slightly smaller scale. The divide is also surprisingly wide among generations. About 71 percent of Boomers who were polled say they’re proud to be American; that falls to 41 percent among Gen Z. (According to another Gallup poll, nearly one in four Zoomers identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer, so I’m not sure what’s going on with that generation, but that’s another story.)

Polling people about their pride in America is a valid question, but maybe not the most pertinent one. If we asked people how committed they are to the idea of America, I suspect the numbers would be much higher. For a democracy to work, we don’t always have to be proud of it — democracy is by definition messy and ever-changing — but we must be engaged in it. Democracy is a participatory sport.

Still, the idea that half the country says they’re not proud of America is startling. After all, we’re the country that instituted self-governance at scale; abolished slavery; saved the world from fascism; created capital markets, airplanes, television, the personal computer, Ernest Hemingway and Aaron Copeland; eradicated polio; deployed the Internet, smart phones and AI; traveled to the moon; and gave the world “Chinatown,” “The Godfather” and the Coen Brothers. What’s not to be proud of?

We’ve made mistakes along the way. We learned that capitalism is capable of excess. We effectively eradicated or subjugated an indigenous population of 3 million people. While we abolished slavery, we enabled segregation for far too long. Enamored with our power, we flirted with empire-building at great expense of blood and treasure. Owning a home, once considered almost a birthright, is getting harder to attain for many people.

Despite all those mistakes, we continue to make progress. In 1925, the average U.S. life expectancy was 59 years; now it’s 79 years. We’ve dramatically reduced the rate and impact of disease and infection with vaccines and antibiotics. In 1925, real GDP per capita was around $8,000 (in 2025 dollars); today it’s $81,000. The U.S. GDP has grown from $100 billion in 1925 to $27 trillion in 2025. And we can buy almost anything we want, whenever we want, and have it delivered to our doorstep in a few days. Plus, “Mobland.”

It’s hard to say that after 250 years America hasn’t made a material, net positive contribution to its citizens and the world.

And yet, almost half of us admit to having little or no pride in our homeland.

There’s a way to fix that. If we were closer together, I’d invite you to the Fourth of July festivities in my hometown of Southport (check out the new Netflix show, “The Waterfront,” for some tantalizing drone shots of our town). We have a parade, fireworks and food trucks, like a lot of other towns, but we also have a dramatic reading of the Declaration of Independence and something else very special — the naturalization of more than 60 immigrants from all over North Carolina. If you see their excitement at becoming new citizens of this country and don’t swell up with pride you need to check your pulse.

All of this contemplation made me realize what a terrible mistake I made in my little art project. It should have been a triptych and included the Declaration of Indepependence with a tri-cornered hat of the time. This audacious document, along with the Constitution, is the source code for the greatest experiment in governance the world has ever seen. I’m proud to be an American. Happy Fourth of July, y’all!

Backatcha re: Happy 4th July, Russ. "I'm a Yankee Doodle Dandy" & "God Bless America" make my heart sing. Trump aside, I'm damn proud to be an American. 1/Lt Brown, 82nd Airborne Div.

Hi Ray. My father was a member of the first paratroopers' classes of the 82nd Airborne. He came from a long line of military in North Carolina, Georgia, etc.