Twilight of the Moguls

Rupert Murdoch and Dean Lesher are very different, but they both shared a passion for newspapers and building

The media-political complex had a changing of the guard this week, one that we saw coming for a long time — Rupert Murdoch, the very definition of a media mogul, retired as chairman of Fox. For all his controversies, and his vilification by the left, Murdoch is a builder who left an indelible imprint on modern journalism. We’ll see what happens now. It may very well be that in a few years Fox News won’t exist as we know it today, but Murdoch’s legacy will only grow over time.

Murdoch’s retirement triggered memories of my own media mogul, the man who created the newspaper that gave me my first job in 1972, an event that would drive the trajectory of my career over the next four decades.

The paper was the Contra Costa Times and the “mogul” was Dean Lesher. In the summer of ’72 I walked into the newsroom and asked if they offered internships for aspiring journalists. I was shown into the office of my first and greatest editor, Art Miller, and walked out 20 minutes later with a job. I returned to school at the end of the summer with an utterly different view of journalism. In school, it had been theoretical, mysterious even; in practice, it was tangible and thrilling. When I got out of school two years later, I immediately walked into a job as a general assignment reporter at the Times, where I stayed for the next 10 years — as a reporter, copy editor, music critic and finally city editor.

Lesher worked out of a large office on the second floor above the newsroom and liked to come down to the cafeteria to rub shoulders with the editorial hoi polloi. Reporters, as a general rule, are an irreverent lot and Lesher came in for a fair amount of snickers and eye rolls. He was portly, he was conservative, and he was wealthy. He catered to advertisers, which provided the lifeblood of the paper, while reporters dismissed them as a necessary evil. In particular, reporters were contemptuous of the annual soirées Lesher and his wife Margaret hosted at their Orinda mansion, where the ink-stained wretches were ordered to act as hosts to the businesspeople and local luminaries who showed up for drinks and canapés.

While the newsroom was busy writing off Lesher, he was busy building an empire.

Lesher grew up hustling. Born in Maryland, he rode in a horse-drawn carriage with his physician father as he made his rounds. He opened an ice cream stand near a local tannery, where he later took a job stretching and tacking hides when he was 12. In high school, he was a shipping clerk for a railroad. His family was wealthy, but he didn’t shy away from work. He went to the University of Maryland and graduated from Harvard Law.

In the newsroom I’d always heard that he took possession of the small paper that was to become the Contra Costa Times in lieu of a legal debt. Not really, although it was a good story. In fact, after Harvard he headed to Kansas City, where he began a law career. (He also became a lifelong friend with a local haberdasher named Harry Truman. In 1945, while calling on Truman to ask a favor, the President said to Lesher, “What are you doing here?” To which Lesher replied, “I was about to ask you the same thing.”)

Lesher became bored with law, but interested in newspapers through his friendships with local publishers. He bought a small paper near Kansas City, but the venture failed. Still young, he headed to California, where he settled in Merced and bought the Sun-Star in 1941. It, too, faltered due to a collapse in advertising during the war years. Restless and unfulfilled, Lesher looked for better opportunities and found one in the Walnut Creek Courier-Journal, a small semiweekly serving an area about 30 miles east of San Francisco.

It was a ride in an airplane that sealed the deal for him.

“It dawned on me that what I should look for here is what makes great civilizations,” Lesher later recalled, factors such as continental edges, riverside locations and, in the case of Contra Costa, the junction of great highways. From the air, he could envision homes in the place of orchards and rolling hills along the Interstate 680 and State Highway 24 corridors.He had no idea just how prescient he was at the time.

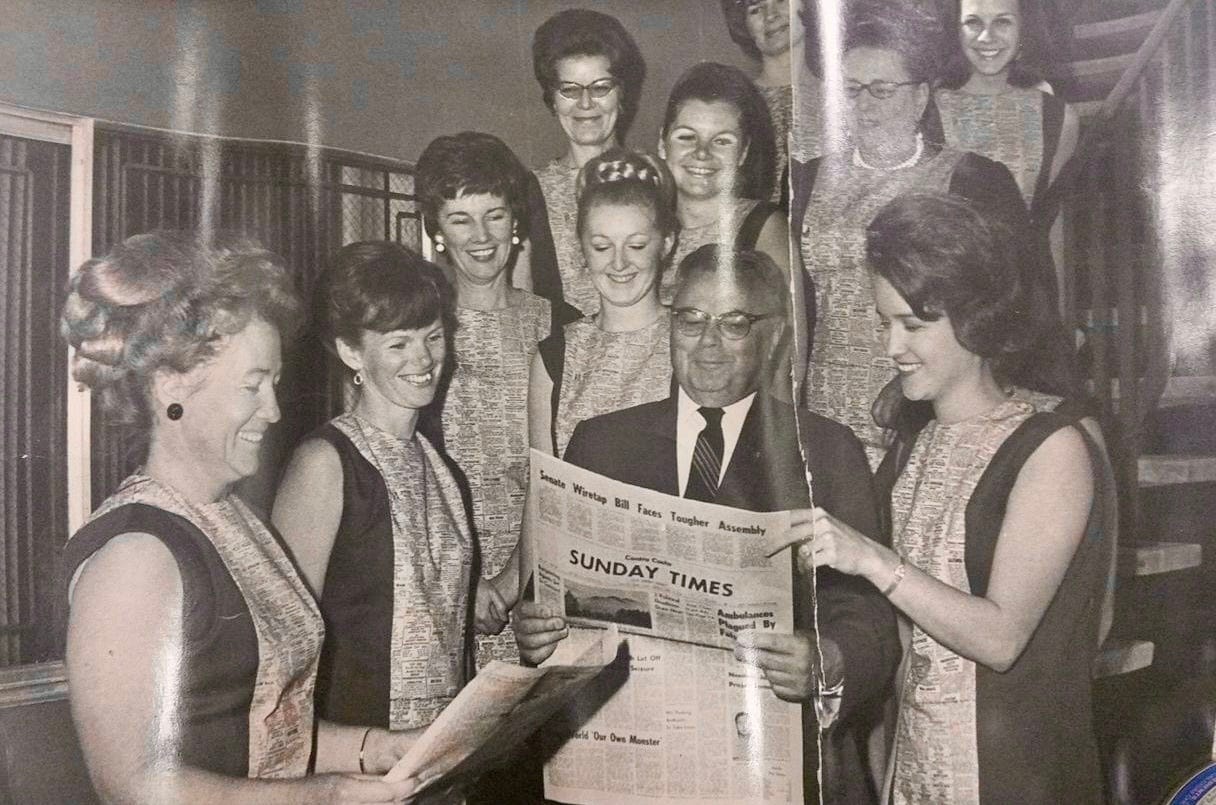

From that point on, Lesher’s career seemed like manifest destiny. He expanded local coverage in the Courier-Journal and became a civic booster extraordinaire. “Rotary, Lions, Soroptimists and Kiwanis service club meetings were featured on the paper’s front pages as well as obituaries and births,” noted an old colleague, Nilda Rego, in an appreciation of Lesher years later. “National news didn’t make it in the Courier-Journal.”

It can be argued that Rupert Murdoch built his career on scandal and titillation. For example, his London tabloid, The Sun, ran daily pictures of topless women on Page 3; his New York tabloid, the Post, is famous for its jugular headlines, such as “Bezos Exposes Pecker,” “Headless Body in Topless Bar” and “Ford to City: Drop Dead.” Lesher’s business model was much more prosaic, but just as effective — he gave the paper away for free, creating a concept called “controlled circulation” that would gradually be emulated nationwide. To stand out, he printed the cover page on green paper, so the shorthand name for the paper, which he had rechristened the Contra Costa Times, was “The Green Sheet.”

Circulation grew, but not necessarily the editorial quality. I recall a story the theater critic of the Times told me when I started at the paper. She was at a cocktail party when the hostess asked her what she did with her time. “Oh, I’m the theater critic for the Green Sheet,” she said proudly. “Oh, that’s wonderful,” enthused the hostess. “I’ve been trying to stop them from throwing that paper in the driveway forever. Can you make that happen?”

Lesher persevered. The paper went daily, he picked up the AP newsfeed and he bought up surrounding newspapers like the Concord Transcript, the Lafayette Sun, the Antioch Daily Ledger and the Pittsburg Post-Dispatch. It was a classic monopoly model and ad rates went up accordingly. Meanwhile, as Lesher had envisioned flying over the 680-24 interchange back in 1947, the central Contra Costa exploded with growth.

He continued buying up local papers in the surrounding area and folded them into a corporate structure he called Lesher Communications Inc. By then, the sleeping giant across the Bay, the San Francisco Chronicle, had woken up. The Chronicle’s premier columnist, Herb Caen, often referred to the “mysterious East Bay,” but the bosses at the Chronicle smelled money and they began a serious push to ramp up circulation. Along with the Oakland Tribune, the competition made for a lively newspaper war. This, of course, was well before the Internet, the Death Star of daily newspapers, when print and TV ruled the news cycle. Lesher’s papers continued to grow and improve. Lesher had become one of the richest men in California and in 1983, Ronald Reagan presented him with the National Newspaper Association’s highest award, for distinguished leadership.

Lesher stayed fairly active until his death in 1993. By the time his heirs sold Lesher Communications in 1995 for $365 million to the media giant Knight-Ridder Inc., that 2,000 circulation semiweekly in Walnut Creek had evolved into an enterprise with dailies totaling nearly 200,000 circulation, a network of weeklies and annual revenues exceeding $100 million.

No account of Dean Lesher would be complete without acknowledging his second wife, Margaret. Murdoch had Jerry Hall, and Lesher had Maggie Ryan. Both were beautiful, flamboyant and much younger than their husbands. Both relished their status as mogul wives. Maggie became notorious in the newsroom for her pointed views on religion and abortion; she once had the newsroom exorcised after a gay city editor was fired.

A 1997 article in the San Francisco Chronicle likened Margaret to Evita, "a beauty, she was born poor, scarred by lost love, elevated to prominence by attaching herself to a man of great wealth and greater ambition, and ultimately vanquished in tragedy."

After Dean’s death, she was remarried to a buffalo trainer and roustabout 25 years her junior by the name of T.C. Thorstenson. Not long after, the two were camping at Bartlett Lake near Phoenix. Maggie didn’t come home. As the story goes, the couple were having drinks then turned in for the night. At some point, Maggie left her sleeping bag to join T.C., who rebuffed her advances. She wandered off and her body was found the next day in 25 feet of water. T.C., of course, was a person of interest, but passed a polygraph and charges were never filed.

Lesher’s life didn’t have nearly the scale of Murdoch’s, but it had many parallels. Both were more or less self-made. They were hard workers with a relentless ambition. And both had a genuine love of newspapers, each edition the product of hours and days and weeks of work, products that helped define the life of a city or nation. Both men were builders. Both put millions of dollars of capital at risk and for both it paid off.

The Contra Costa Times no longer exists today. It and its sister papers have been rolled up into something called the East Bay Times, which is no doubt struggling along with every other mid-sized paper in America. But for a very long time, Lesher ran an enterprise that was inextricably tied to the growth of one of most vibrant and affluent regions of California.

I like to imagine him, late in life, flying in a plane over Contra Costa County, maybe sipping a Viano wine from the vineyards around Martinez, saying, “I built this. I envisioned it and helped create it. I’ve done my work.”

-30-

(Thanks to the Media Museum of Northern California, Nilda Rego and Wikipedia for valuable background on Dean Lesher. Journalism is a collaborative effort.)

Great story, Russ! I worked there from 1980 through 1998. I used to to eat lunch with Dean in the cafeteria almost everyday until he retired to his home. He told some of the best stories, that were actually the history of Contra Costa. These were the golden years of the newspaper life. I was glad I was in it. I feel fortunate to have worked with all those great people and Dean Lesher. Like you, Russ, it changed the trajectory of my life. Working nearly 20 years in journalism and the technology of the industry and going on to teaching and managing technology at the Graduate School of Journalism at Berkeley for another 20 years. Thanks Russ, for a trip down memory lane!

Thank you for this history, Russ and for making sense of it! I didn’t know you’d worked for the CC Times. Dean and his first wife Kathryn were our neighbors in Lafayette, when I was growing up. Thanks I am sure to my mom asking him, Dean gave me my first reporting opportunity, when I was 15. I covered a Republican Governor’s Association conference in Palm Springs in 1968, for the CC Times, my first commercially published article. Met R Reagan, R Nixon, G Ford, Walter Annenberg, etc. My mom later became friends with Margaret. When my father wanted to buy that house in Orinda, my mom said no - too expensive and too much upkeep - and told Margaret about it. She and Dean became the owners and moved in, to my mom’s relief!