In the space of an hour over the weekend I received two emails that spoke volumes about the state of America today.

The first was from a friend in Northern California who forwarded a piece from the New Republic titled: “Trump’s Military Parade Was a Pathetic Event for a Pathetic President.” My friend only had a brief comment. “Shall we weep in unison?” he asked, a little rhetorically. The second email came through a few minutes later from my cousin in Southern California, who forwarded a report from Fox News headlined: “Military Parade Draws Patriotic Americans from Near and Far.” He too, had only a brief comment. “We watched it and thought it was well done,” he wrote. “Even when it rained!”

And, of course, while anywhere from 25,000 to 250,000 people, depending on who you believe, were watching the parade, 2 million or more turned out for “No Kings” demonstrations across the country. Cue whiplash.

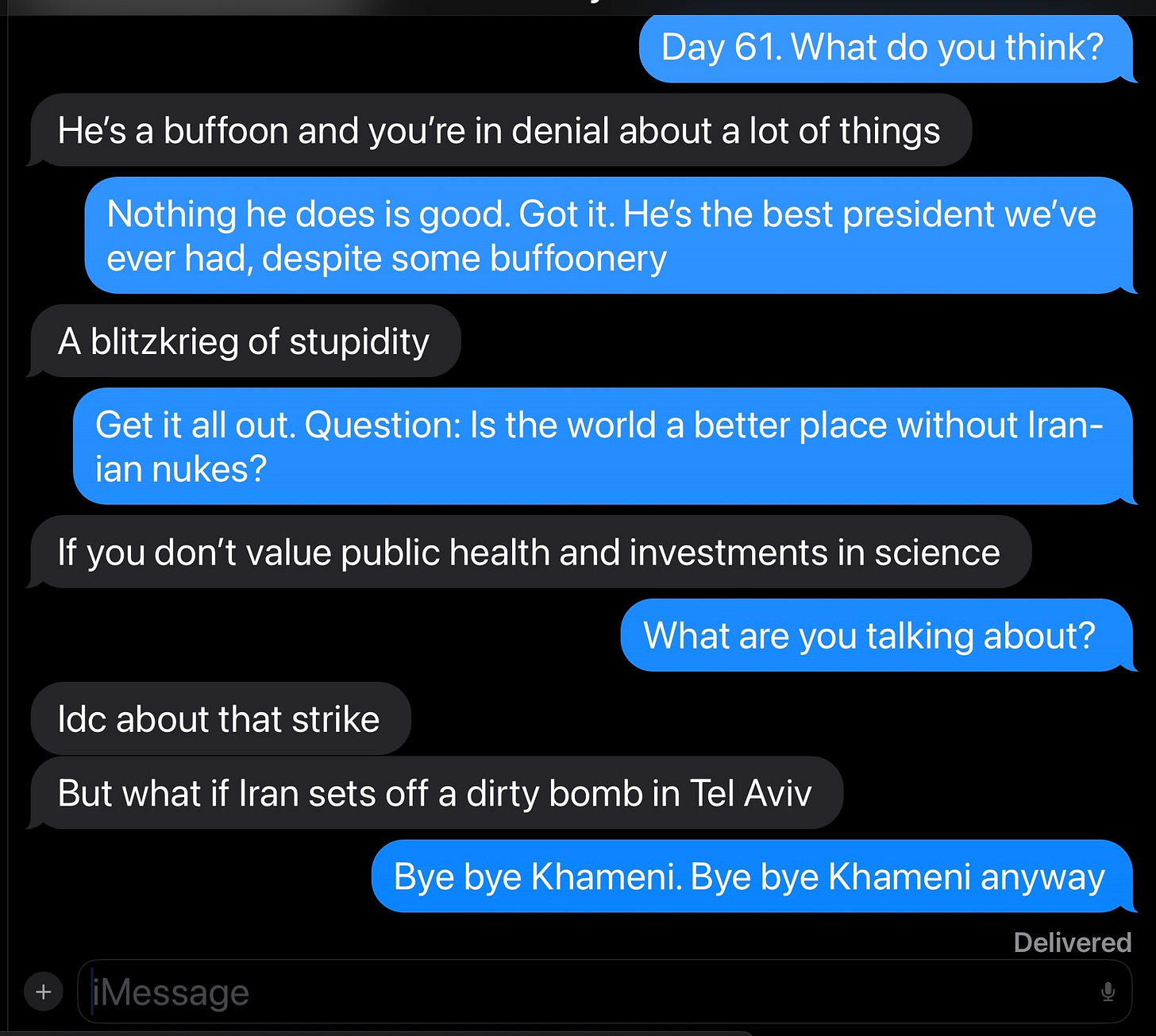

The day before, a friend shared a screen shot of a text conversation he had with a mutual friend regarding Trump. Here’s a snapshot, with the identities masked.

The point I’m making — that America is polarized — isn’t news. Our current state of polarization began in the mid-90s with the so-called Republican Revolution, when the GOP took control of the House for the first time since 1954 and shifted the center of gravity in Washington. Newt Gringrich became the spiritual and legislative leader of this new generation of Republicans and quickly began defining the culture of polarization. Republicans, he insisted, were not to fraternize with the opposition, whether it be working on bills or going to lunch or church socials together. Ronald Reagan and Tip O’Neil liked to share the occasional joke and wee dram in the Oval Office; no more, dictated Gringrich.

In 1990, Gingrich issued a manifesto titled "Language, a Key Mechanism of Control,” which encouraged Republicans to "speak like Newt.” It contained lists of "contrasting words" — those with negative connotations such as "radical,” "sick," and "traitors" — and those he called "optimistic positive governing words" such as "opportunity,” "courage,” and "principled,” that Gingrich recommended for use in describing Democrats and Republicans, respectively.

First came language, then came strategy. “Gingrich and his allies believed that an organized effort to intensify the ideological contrast between the congressional parties would allow the Republicans to make electoral inroads in the South,” wrote political scientist David Hopkins. “They worked energetically to tie individual Democratic incumbents to the party's more liberal national leadership while simultaneously raising highly charged cultural issues in Congress, such as proposed constitutional amendments to allow prayer in public schools and to ban the burning of the American flag, on which conservative positions were widely popular — especially among southern voters.” With a few linguistic modifications (e.g. substitute working class for southern), this is exactly the Trump political playbook.

In this context, it’s easier to understand the dramatic drift in polarization that began in the mid-1990s.

As the polarization gap grew in quantity, it took on new and disturbing qualities. It became emotional. In the new polarization, it wasn’t enough merely to disagree with the opposition on a policy. Polarization became personal, or what sociologists call “affective.” In poll after poll, when asked to describe the other party, each side began using terms like “closed-minded,” “immoral,” “lazy” and other pejoratives. Emotional judgment began to crowd out safe places in the center like reason and respect. Motives were questioned. Trust became roadkill.

A spectacular and recent example of affective polarization was the midnight tweet from ABC news correspondent Terry Moran, who posted that Stephen Miller, the White House deputy chief of staff, was “richly endowed with the capacity for hatred.” Moran added that Mr. Miller “eats his hate” as “spiritual nourishment” and assigned the term “world-class hater” to both Mr. Miller and President Trump. Moran may have thought he was speaking truth to power, but his bosses didn’t appreciate the way he broke the fourth wall of journalism, shedding objectivity like an empty can of beer. He was fired.

The novelist and essayist Marilynne Robinson is so affected she suggests we’ve moved beyond polarization to a state of “occupation,” as in the Red occupying the Blue. “These people who call themselves conservative are root-and-branch radicals,” she wrote in The New York Review of Books. “So it is time to face the fact that their demolition of government and society as we have known them more strongly resembles a hostile occupation than a normal presidency.”

Polarization distorts reality, to the point where even reasonable political initiatives — like making government cheaper and more efficient — become lightning rods. Or challenging patently bad ideas, such as rounding up Latinos at Home Depots and farms for deportation, becomes treasonous. Polarization forces us into positions that we can’t defend, but must, leading to a toxic spiral.

Without the kind of emotional forbearance that reason and respect enable, we’re stuck in a doom loop of polarization. If polarization effectively began in the halls of Congress in the 1990s as a political strategy, it began to metastasize more broadly in society with the advent of social media. The algorithm made polarization pernicious. Thirty-five years after Gingrich’s manifesto, the language of division has become embedded in the culture. Polarization has gone from pernicious to permanent.

Social media has supercharged the effect. Algorithms prioritize engagement, boosting content that provokes strong emotions—anger, fear, or outrage—over balanced discourse. A 2025 analysis of X posts revealed that partisan rhetoric, such as debates over Donald Trump’s 2024 campaign themes (e.g., “border security” and “fake news”), garner significantly more interaction than neutral topics. This creates echo chambers, where users are fed a steady diet of reinforcing opinions, while cross-cutting exposure diminishes.

“Fake news is an overhyped issue,” wrote Andrey Mir, more succinctly. “The greatest harm caused by media is polarization, and the biggest issue is that polarization has become systemically embedded into both social media and the mass media. Polarization is not merely a side effect but a condition of their business success.” In a hypermediated society like ours, this should concern all of us.

We can’t escape polarization by blaming the other side. Nor can we just ignore it, waiting for it to heal itself. This is up to us. Political leaders need to reject the language of polarization. In this regard, Trump, the current occupant of the bully pulpit, is a lost cause. It was 10 years ago this week that he announced his candidacy by declaring, among other things, that Mexican immigrants are “rapists.” He’s been ramping up his language ever since.

Democrats too have fanned the flames. Rashida Tlaib, a Muslim congresswoman from Michigan, set the tone six years ago when she made a sordid threat against Trump: “We’re gonna go in there and we’re going to impeach the motherf—r.” Nor is it credible for Gov. Tim Walz to denounce political violence as he did in the wake of last week’s assassinations in Minneapolis, while just a few weeks before he had publicly called on Democrats to “bully the shit out of Trump.”

There is a middle way — not over or under, but through. The biggest tent in American politics is in the center, but we don’t recognize it anymore because fewer and fewer of us live there. Living in the center requires reason, respect, patience. And a modicum of courage, because living in the center means that we might have to change our minds occasionally. But the result of an authentic commitment to the center pays dividends in terms of resiliency and progress. Solutions at the margin are usually driven by ideology or allegiance; solutions at the center are driven by collaboration, compromise and empathy, all of which are core to the American character. Polarization is bound by binary thinking — either you’re with me or against me. The middle way embraces “spectrum thinking,” which allows for nuance, alternatives and possibilities. It shifts the conversation from “Yes, but” to “Yes, and.”

John Fetterman is a good, if flawed, example of this kind of free-range approach to political orthodoxy. But we need bigger and better models of the middle way, people who are willing to stand up and say “Yes, and” over and over, who show respect to those they disagree with, who acknowledge an opponent’s aspirations even if they disagree with the methods. Because at the end of the day, we’re all bound by the same aspirations — security, prosperity and community. The best and current example of moving in this direction is Ezra Klein’s new book, “Abundance,” which urges us to throw off the shackles of ideology and identity in favor of pragmatism and consensus.

Is all of this too naive? Maybe. History has shown that even the loftiest language can’t always avoid conflict. “We are not enemies, but friends,” Lincoln famously said in his first inaugural address. “We must not be enemies. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” Six weeks later, the Confederacy attacked Fort Sumter.

But we can try. If we want to build a future for our children and grandchildren, and their children, we have no other choice.

Peace out.

Musk's idea for a third party might be the ticket to get all the centrists that you allude to, to vote in a Prez, as long as Musk doesn't trot out himself as candidate. Someone like Jesse "The Body" Ventura would be great.

A lot of good points; I’ve debated with friends the current echo chamber of social media and how “twitter makes us bitter. “

But I think the divide, started earlier and driven more by issues than tone and rhetoric, most notably abortion rights. At the time of Wade (1973), the main parties were more like 60/40 and 40/60 (maybe 70/30 and 30/70). By 1992, abortion had morphed as a litmus test for candidates for both parties. The silencing of Gov Casey at the 1992 convention wasn’t about the right words to use but what issue could come up for debate.

Tone and rhetoric are basically campaign tactics. Change a few minds but mainly raise money and drive turnout.